My favorite time to obsess about my parenting choices is when I’m washing dishes, a mixture of warm soapy water and tomato sauce soaking my belly. Am I raising my six-year old right? Should she be doing more than yoga and dance? Or is she already too busy? Does she have time to let her mind wander? Should she be helping me with the dishes? Or would she be better off making mud pies?

Then I began reading Rice, Noodle, Fish, by Matt Goulding. The subtitle to this book is not Parenting for Chefs… Nor did Anthony Bourdain Books / HarperCollins, the publisher, intend this book to have an interdisciplinary application.

But the best books do.

This is not some gentle text.

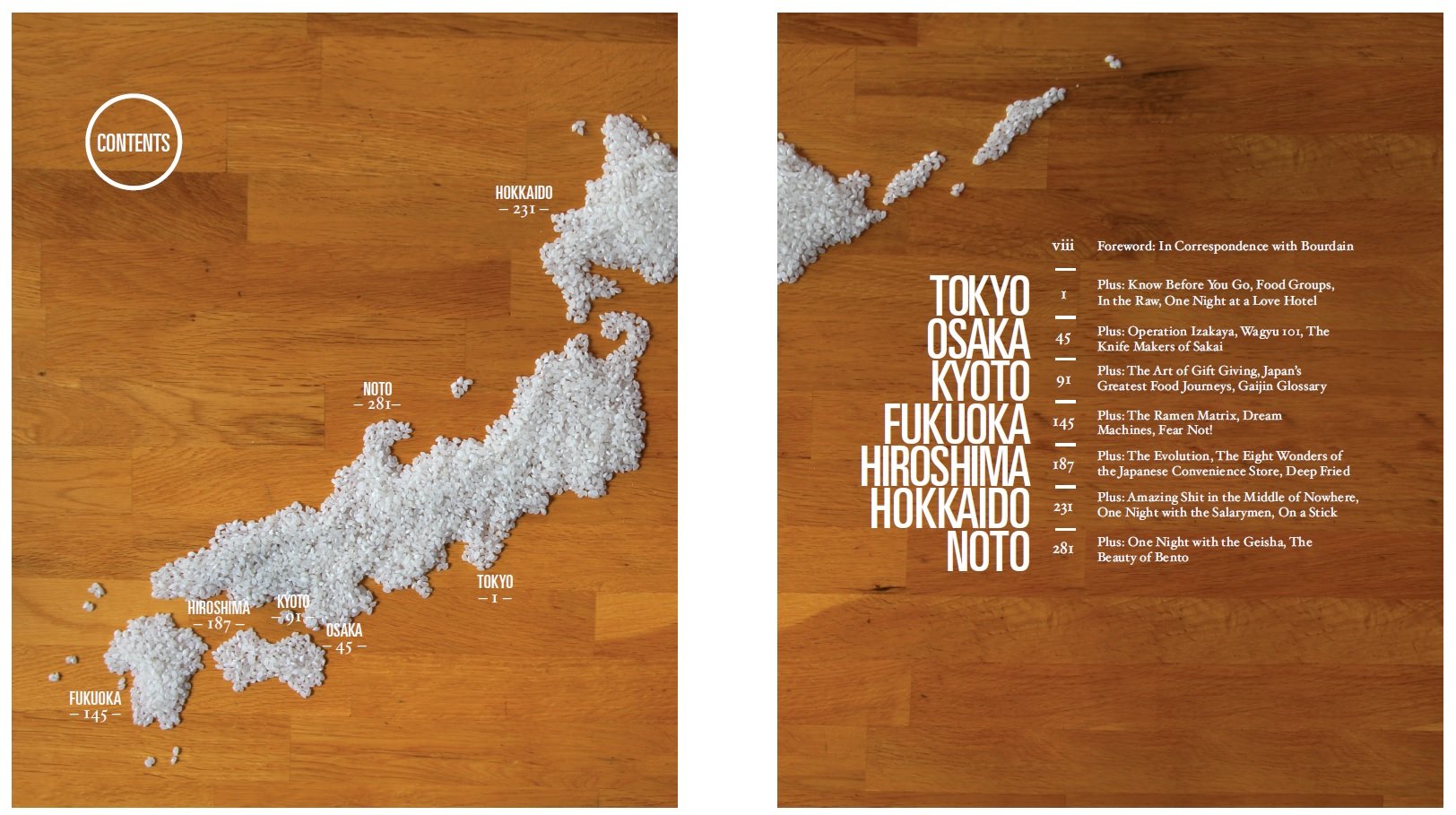

Pursuant to the actual subtitle, Deep Travels Through Japan’s Food Culture, this is not some gentle text, allowing the reader to sit comfortably in whatever generalist assumptions we might have about Japanese cooking. This is a 1,000-x magnification, showing crumb-level texture of the food scene in several major Japanese cities. From Tokyo to Noto, we sweep quickly past what we already know – ramen, udon and tempura – to get to know the people and their craft. The imagery is vivid and the language, at times, is colorful. There are lessons in the elaborate art of knife making, and details about why Japanese chefs believe “water is the most important ingredient in Japanese cooking.”

(Don’t be too quick to dismiss this concept – local water has it’s own flavor and is one reason why bagels, pizza, sour dough, and sushi rice tastes different from city to city. It’s also the reason why iced tea made with city water tastes no better than a slightly sweet mud puddle)

The main idea?

Simple.

Devotion is the core of Japanese cooking.

In Rice, Noodle, Fish, food is the mechanism to get at the process of Japanese cooking and, with this, the book reveals a distinct way of being oriented around the idea of DEVOTION. Even the author’s dedication points to this:

To the shokunin of Japan, pursuers of perfection, for showing us the true meaning of devotion.

What is a Shokunin?

The concept of shokunin, an artisan deeply and singularly dedicated to his or her craft, is at the core of Japanese culture. […]

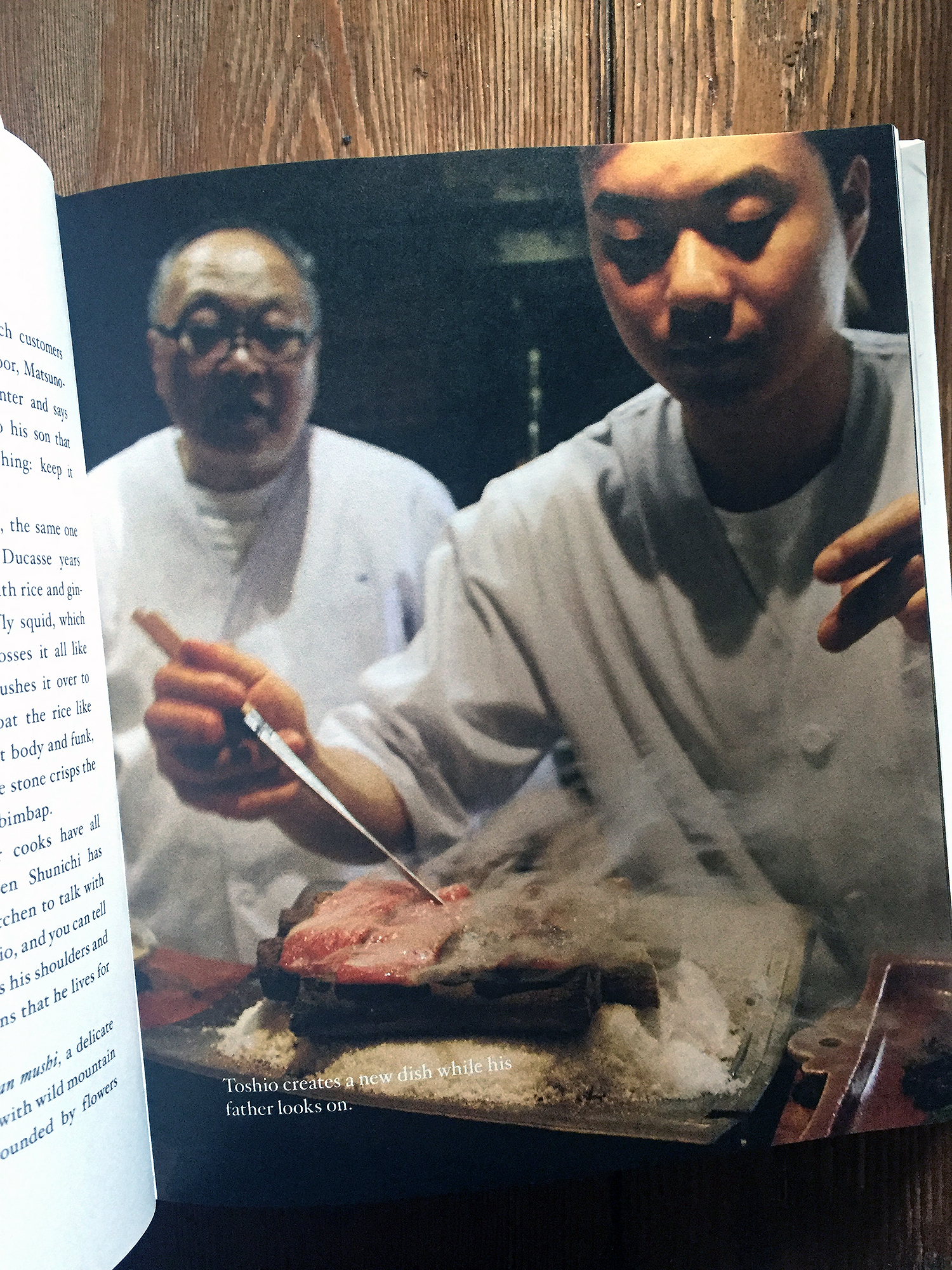

Hiding in every corner of this city and country: the eighty-year-old tempura man who has spent the past six decades discovering the subtle differences yielded by temperature and motion. The twelfth generation unagi sage who uses metal skewers like an acupuncturist uses needles, teasing the muscles of wild eel into new territories. The young man who has grown old at his father’s side, measuring his age in kitchen lessons. Any moment now, it will be his turn to be the master, and when he does, he’ll know exactly what to do. […]

Tokyo is the city of ten thousand shokunin. If you come to Japan to eat, you come for them.

– Rice, Noodle, Fish: Deep Travels through Japans Food Culture by Matt Goulding.

Accidental Lessons in Parenting (from Japanese culinary masters)

Between mouthwatering reading sessions and fighting the urge to hop on the next flight to Japan, I found myself thinking about the concept of shokunin – DEVOTION – in relationship to how I parent my daughter. Here are a few rules from Japanese culinary masters that also apply to parenting:

1. Parenting with Kimochi, or FEELING

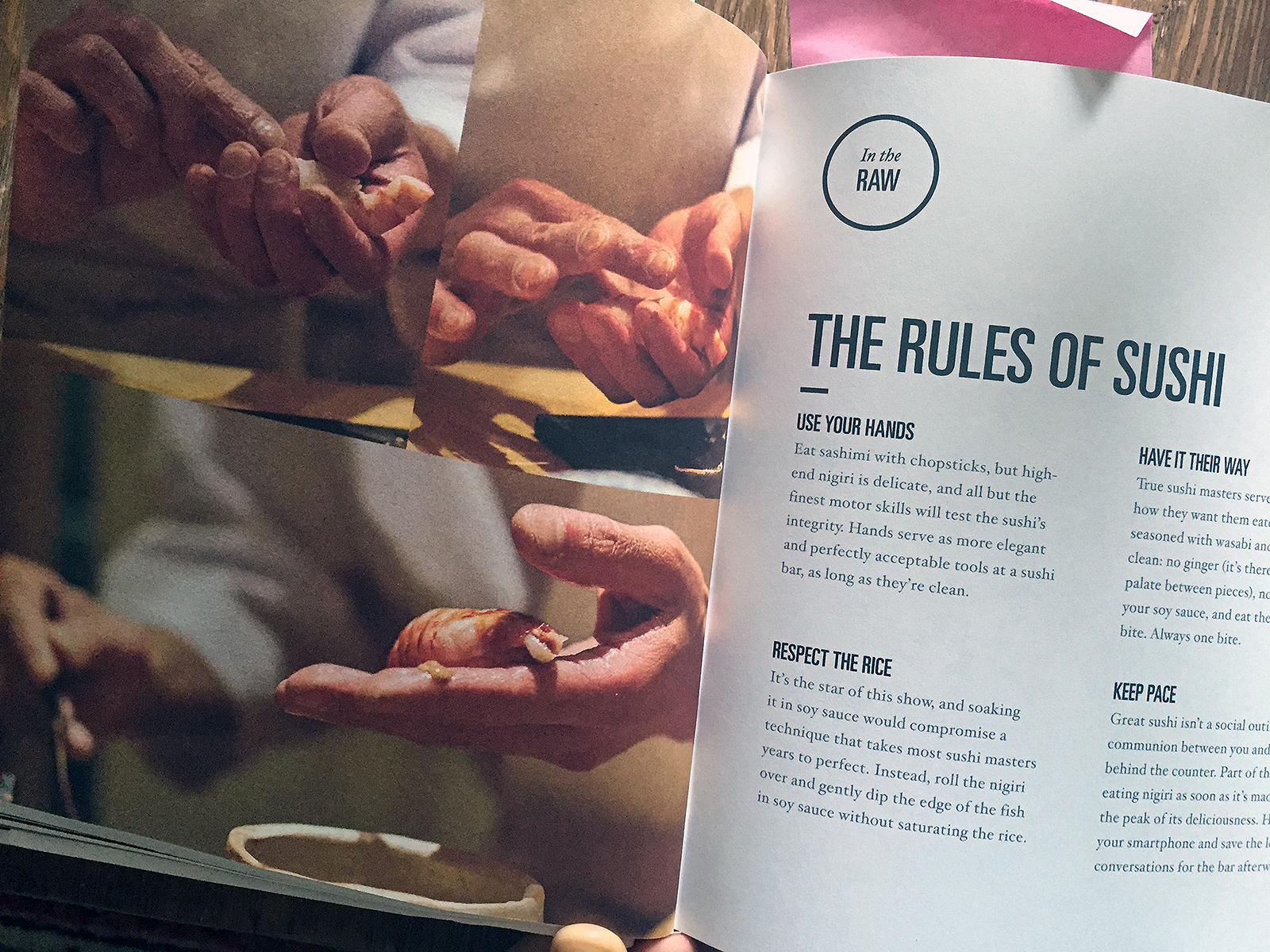

The best sushi comes down to feeling. With only two primary ingredients, rice and fish, rice is the harder of the two to master and, therefore, the true star. According to master sushi maker Sawada, sushi rice should be skin temperature, served 60 minutes after cooking, and made with the best rice from the exact right location (a site that recently changed because of global warming). He says there is no fire – it is made with the hands, and enjoyed with ours, sushi is all about feeling.

As with sushi making, there are two primary ingredients in parenting: You need the parent and you need the child. Like turning rice into sushi rice, a lot of parenting decisions are based on FEEL. A child throwing a fit will warrant a different reaction based on the why, the where, and the how. Reacting appropriately gets easier the longer we parent. Having a standard – as Sawada does – helps give parents a baseline for their reactions.

2. Lessons are not learned in isolation

Just like the shokunin, it is not enough to tell our children what’s what. We need to stand side by side with our youth, demonstrating by example, guided by a set of principles based on quality and consistency.

Many of us want to tell our children to do something and have them march off and do it. Clean your room! Put away your back pack! Brush your teeth! But the shokunin became masters through repetition at the side of a mentor, or master. It is sometimes more effective to have a young child brush their teeth at the parent’s side while the parent brushes their own teeth than griping at them from another room. Equally, a young child benefits when we clean their room together – so that, by the time they are old enough to do it themselves, they have positive associations with the experience.

In every instance, children benefit when we model the behavior we want them to cultivate. Many times they absorb the lesson without realizing one has been taught – as when we model loving language towards friends and strangers; as when we let them see us struggle with tough decisions. Side by side, we give our children a framework for how to cope with the many circumstances life throws their way.

Side by side, they get the feel.

3. Learning doesn’t stop at 18

Let’s return to the image of the fledgling Japanese chef: “The young man who has grown old at his father’s side, measuring his age in kitchen lessons. Any moment now, it will be his turn to be the master, and when he does, he’ll know exactly what to do.”

Do you see how the chef is already old, and yet he is still not a master? The same is true in the photo above, which mentions that decades of study does not guarantee a master.

I’ve noticed a quickening among the youth around me. I see that they are so eager to get in the workforce and to be valued, both by the dollar and their title. But with this rush comes impatience – as though there is no time for mastery, only success. The parent’s job is to continue teaching, even after their child turns 18. And some of those lessons, I assure, will have been taught many times before. Repetition gets the child to mastery.

4. Don’t try and give your child every opportunity

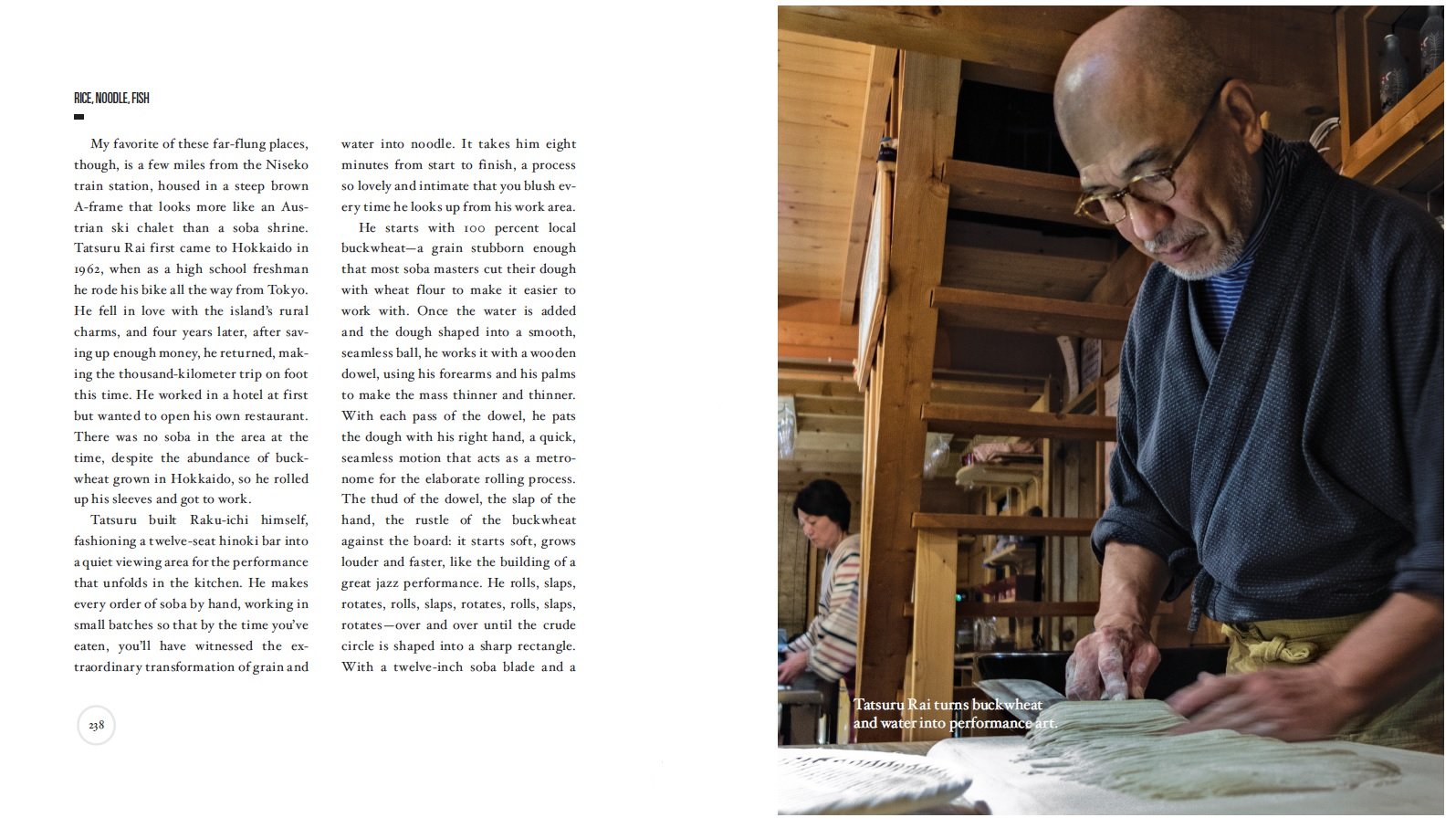

One of the most important aspects of being a shokunin is the ability to specialize in one thing. The shokunin is an artisan “deeply and singularly dedicated to his or her craft.” You make ramen. Or you make sushi. You forge knives. Or you work buckwheat into soba noodles. The master knows they can never be best at everything so he or she CHOOSES.

So many of our children are driven around from activity to activity, like so many worker bees, moving too quickly to settle into any one activity. But even bees are focused on one thing: making honey. In our fear that our children don’t have every opportunity they become generalists. This is not, in and of itself, a terrible thing. Not everyone in Japan is a master, nor should every person be a master.

But what happens when an entire culture – a.k.a. ALL THE PEOPLE – rely too much on speed and productivity (MORE, MORE, MORE!) and not enough on taking time to develop a deep understanding of their craft?

Automation. Disintegration. That’s what.

I say it’s time to return to artisan ways. To learning something really well, from someone who knows it really well.

And, hey! What if we let our children’s natural abilities guide what activities they choose? Any given season of a young child’s life, let them focus on one, maybe two activities. Fall could be ballet. Spring could be softball and theater. When we limit our children’s options, we give them time to learn at a deeper level.

We also make time for mud pies and impromptu puddle stomping.

5. That means you, too

Let’s return to our sushi master from #1. His desire to offer the best possible sushi leads him to serve only 12 people each day, at a bar that seats six. Get this: he used to seat 8 people, but felt that was too much. He gets up at 6 am and goes home at midnight. All to make sushi.

Sound crazy?

Or does that sort of devotion seem somehow magical?

Here’s something to consider:

Where are you, the parent, spending your hours?

Who are you serving with your time?

Is your job draining your energy? Are you involved with too many groups? Or do you need to get out more, so that you can be refreshed when it comes to the family? Emotionally, you might be trying to “serve 8” and finding that something has to give. Parents are as likely to overexert themselves as their children… so do take the time to remove a couple extraneous “seats” in your life if you find you are overdoing it.

What it all means

Look, I know a book on Japanese food is probably not where you want to get your parenting advice. And I know Matt Goulding had no intention for Rice, Noodle, Fish to be used in this way. Writing this post, I thought, more than once, that I might be crazy. But I honestly think the premise applies.

Here’s the bottom line:

We can all use a little more devotion in our lives – not to become more devoted to our children, because goodness knows we wouldn’t be shuttling them from activity to activity if we weren’t – but to actually model devotion as a choice to DO LESS with MORE PASSION.

I, for one, am willing to try.

Thanks, Matt.

And thanks to the shokunin for showing the way.

Photos from Rice, Noodle, Fish.

6 Comments